Design Decisions: Cutting Cubes from Clouds

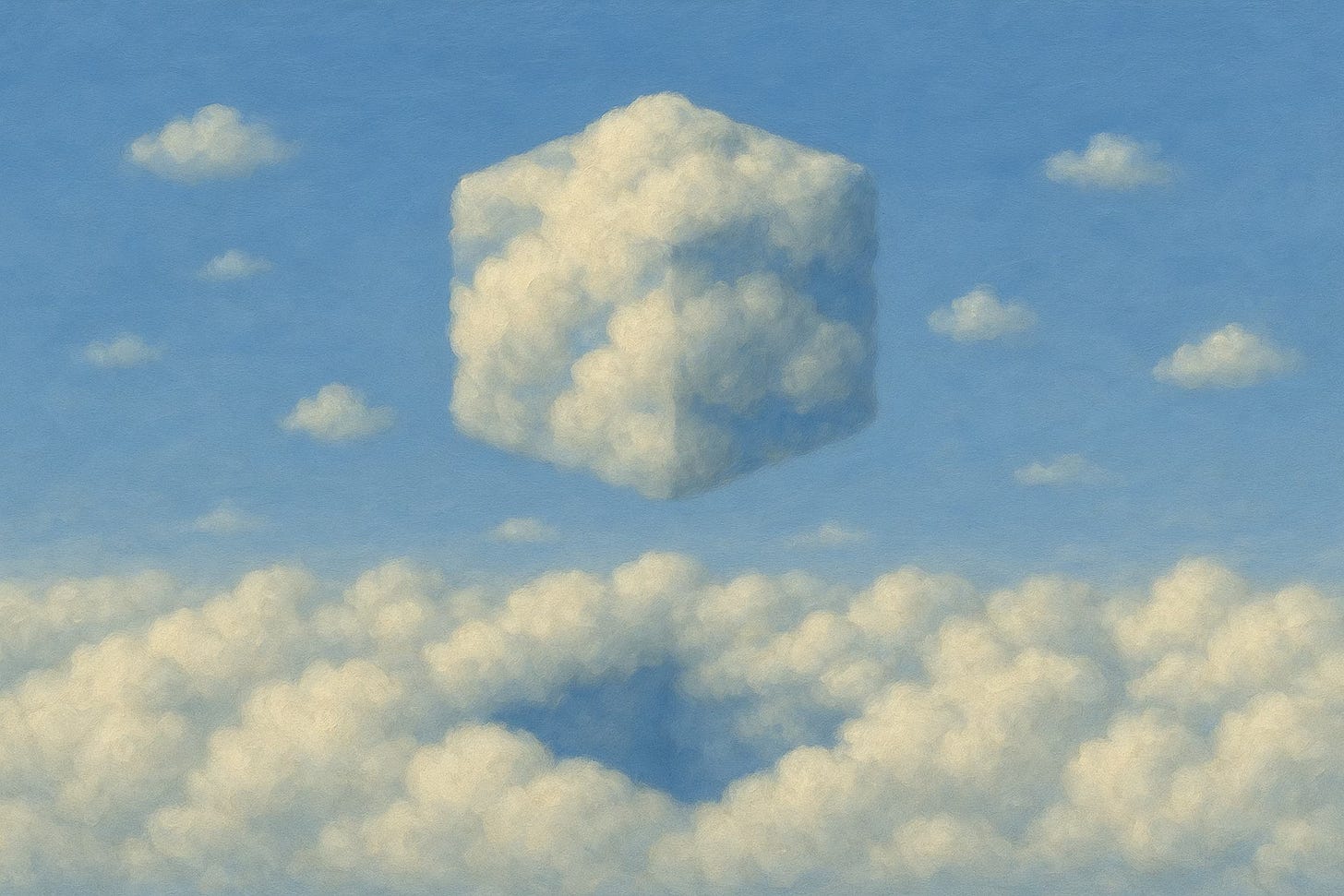

When you’re stuck and you can’t see through the clouds, you need something to believe in.

In a previous article, I reflected on the Double Diamond model of the design process—its widespread adoption and its familiar phases of Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver. When I discovered the Double Diamond, it was exactly what I was looking for—a framework for understanding what I was trying to achieve as a designer. Then I lost my faith. I found the Double Diamond set the wrong expectations and offered little guidance for the most difficult and even painful parts of the design process.

You might want to read that one first…

After that, I needed something else to believe in.

This piece introduces the framework I developed when the Double Diamond failed me. I call it Design Decisions—a way to think of design work not as a sequence of phases, but as types of decisions. When I don’t know what to do, this is what I do.

So many decisions

Every design project involves an essentially infinite number of decisions—each made with wildly inadequate information. It can feel like flying a plane into a cloud bank with zero visibility, the instruments failing one by one. Even simple projects demand choices about goals, constraints, research, and which ideas to pursue, each decision nudging the work’s trajectory. Often, each team member develops a different mental model of the project—what's been learned, what matters, what should happen next. Without a shared point of view—everyone arrives at their own perfectly rational, but often conflicting, perspective on the way forward.

Once I noticed this pattern, I saw it all the time.

If I could help teams with design decision making, maybe there would be less panic and consternation on complex design projects. Maybe we could rely less on a charismatic leader with broad sweeping hand gestures and dramatic intonation of voice to tell us what to do. Maybe we could just figure it out ourselves?

This is what motivated me to look more closely at the decisions that shape a project.

The Design Decisions Framework—Navigating Ambiguity in Design Practice

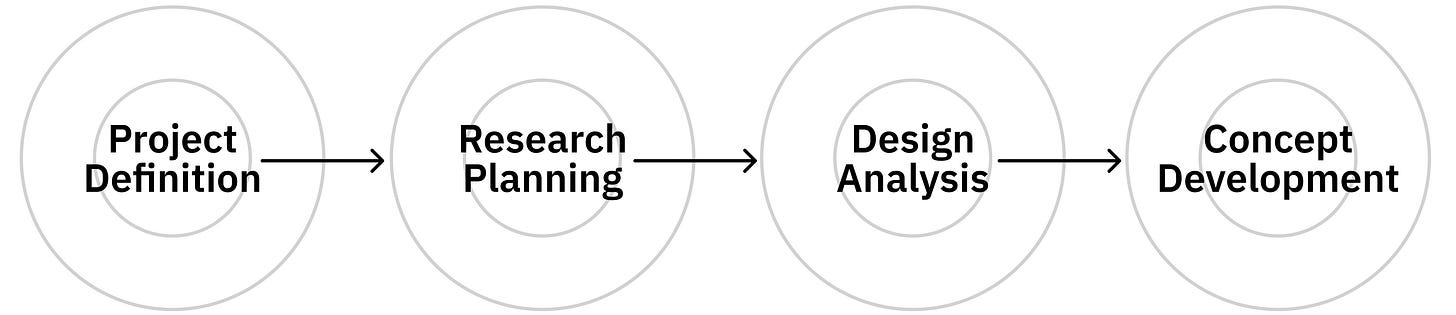

While the number of choices in any design effort can feel infinite, I believe there is a pattern: design decisions cluster into just four fundamental types. Those four types of decision became the foundation of the model I now use in practice and teach in my graduate courses in interaction design.

There’s a logical structure…

Each type of design decision sets the context for the next. When you have a sense of your goals, you can have a point of view on what you need to learn. When you’ve learned things, you need to understand what it means for your project. When your insights spark ideas, you need to nurture and develop those ideas. There’s a logical structure to the decisions.

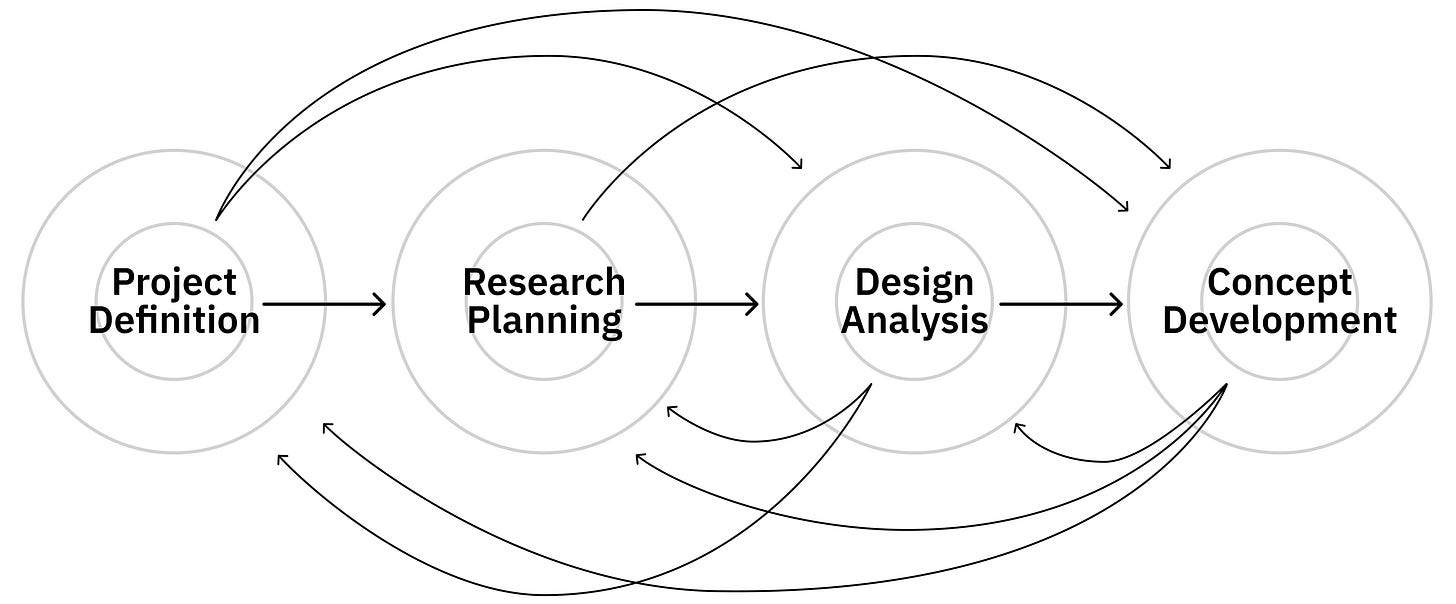

But It’s Not a Linear Process

Project information rarely arrives so conveniently. New data, constraints, or insights can surface at any time—forcing teams to revisit earlier decisions. Design analysis might reveal insights that make you rethink the project definition. Late-stage prototype concepts might reveal gaps in the original research plan or project defintion.

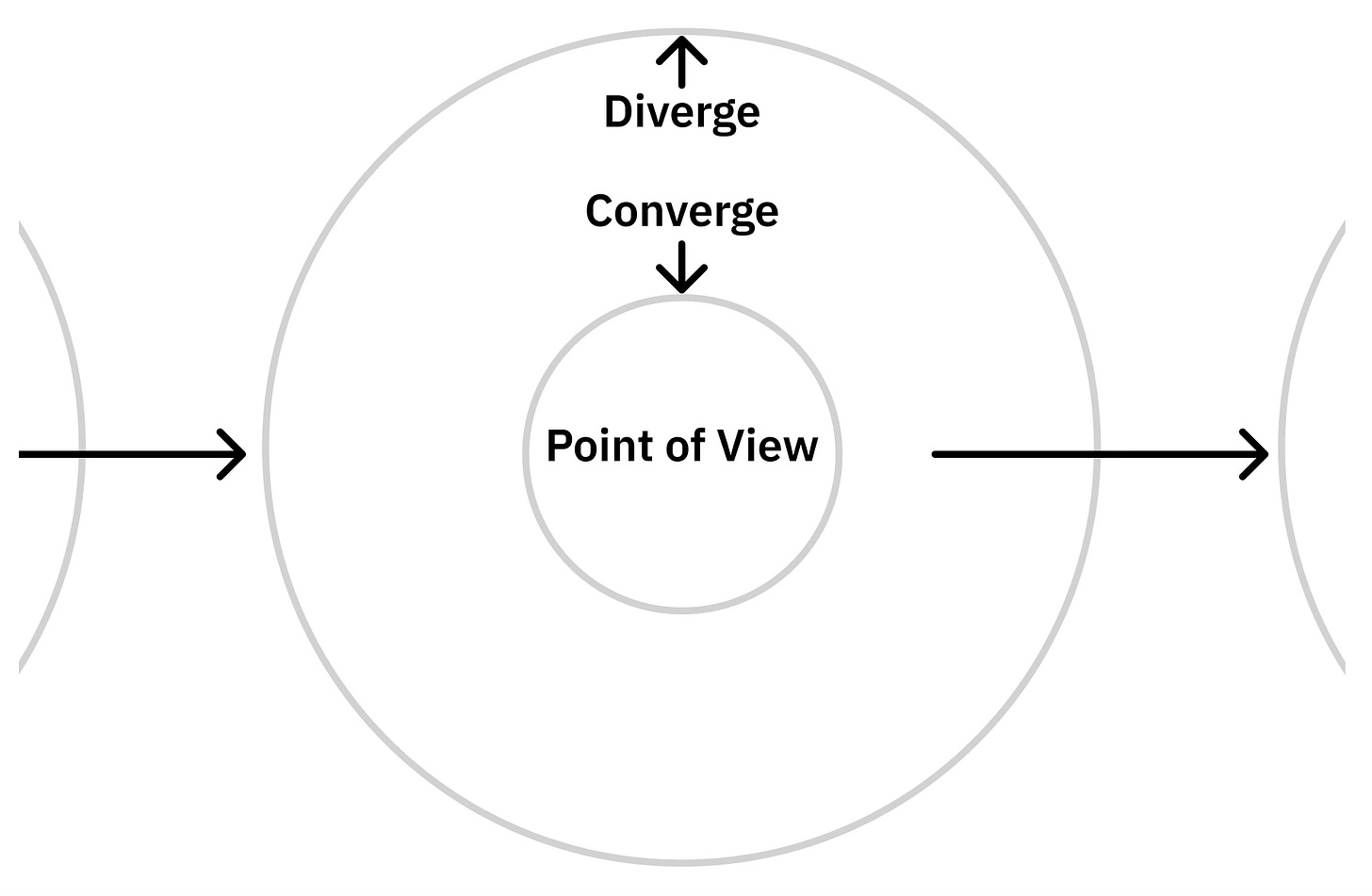

Convergence and Divergence

Each of the four decision types require constant divergence and convergence. If you’re familiar with the Double Diamond, you’ll recognize this pattern: first there is an exploration, then a distilling. This happens twice in the Double Diamond model, thus the two diamonds.

The pattern is real, but I think it happens across each of the four decisions, and it happens over and over again not only twice.

For each decision type, teams begin by stretching the boundaries—deliberately exploring a wide range of possibilities, interpretations, and perspectives. This is important because sometimes you don’t know where you want to be until you’ve gone too far.

Developing a wide range of options gives the team something real to reflect on. Then the group can converge—negotiating trade-offs, and arriving at an actionable point of view.

It’s a Learning Process

In practice, convergence is always provisional. Any point of view can be re-opened. Teams don’t move cleanly from left to right; they loop, reframe, and adapt continuously based on what they learn.

That’s not a flaw in the process. That is the process.

Teams feel discomfort when they try to force the design process into rigid phases and timelines. We want the work to be predictable. The Double Diamond seems to offer this certainty, but it’s a lie. We want to stay on track, but design resists that neatness. I’ve come to believe we need to work with that reality, not fight against it.

Experience helps. Over time, you get a better feel for how a project might unfold. But even after 25 years of practice, I rarely commit to a fixed plan beyond a few weeks at a time. Who knows what we will learn after we get started? I’d rather stay responsive than pretend I know more than I do. When someone commits to a long project timeline, I know to take it with a heaping shovelful of salt.

The Four Frameworks: Making Project Knowledge Tangible

Sometimes, I use my framework quietly. No one on the team necessarily knows this is what’s going through my head. But when I’m helping a team navigate a project, I’m organizing the four types of information—trying to give the team a shared point of view on what’s been learned.

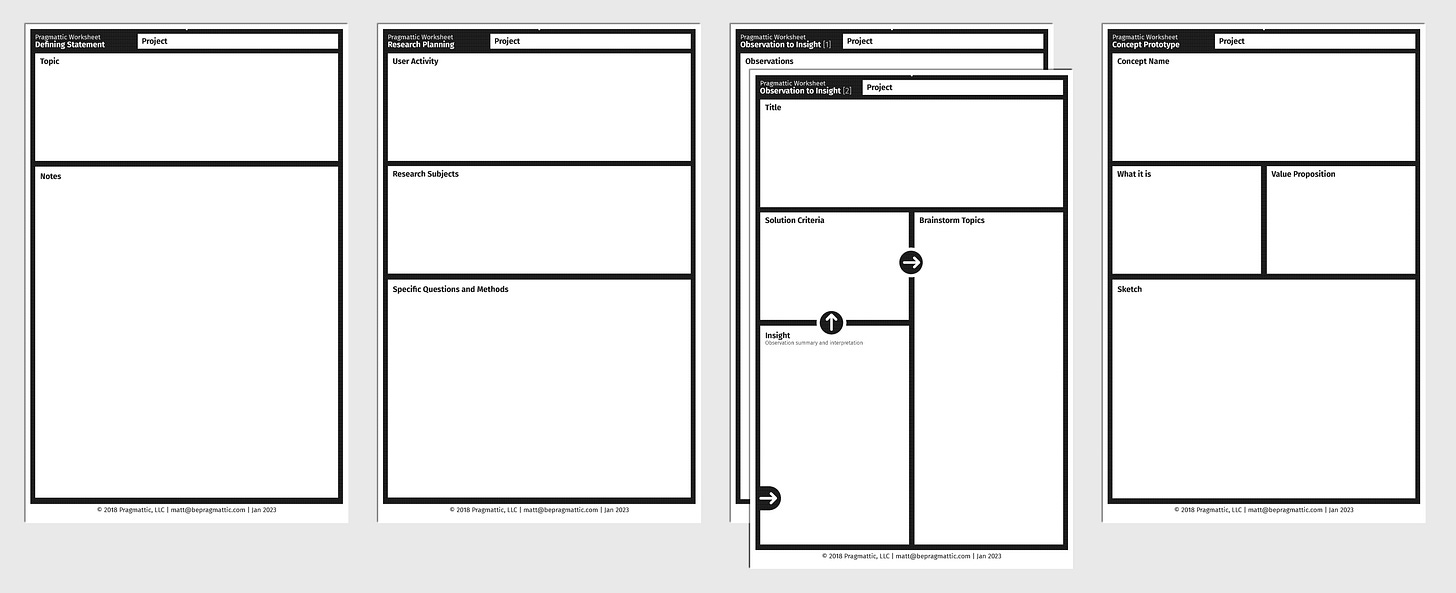

My preference, however, is to fully enlist the team in the process because I want everyone’s input. I’d bet on the collective intelligence of a team over the myth of the lone design genius any day. To make the Design Decisions framework more actionable in team settings, I developed four more detailed sub-frameworks, each tailored to a specific type of decision.

These frameworks help give a useful form to cloudy design project data, allowing you to understand what it’s made of and what it looks like from different perspectives. They make project knowledge tangible, helping teams build a shared understanding of what they’ve learned—and keeping that knowledge within reach when it’s needed most.

1. Project Definition: What Are We Doing?

The Project Definition framework helps teams clarify project goals and document how they evolve. It focuses on capturing a priori requirements—those defined by strategic, organizational, or external constraints—rather than the goals and criteria that emerge through the design process itself.

This framework guides teams to capture three types of information generated during project scoping conversations:

Goals & Requirements — What’s the business intent? What are the known user needs? What constraints or success criteria are already known?

Activities & Roles — How long is this expected to take? Who’s involved, and who’s responsible for what?

Deliverables — What are we making? And who needs to do what with those deliverables when we’re done?

As the project develops, periodically revisit this collection of statements to stay aware of changing scope and evolving goals. A project is “defined enough” when everyone understands the boundaries well enough to move into research planning.

2. Research Planning: What Do We Need to Learn?

The Research Planning framework helps teams generate potential research tasks grounded in learning objectives. First, it is a divergent exercise: teams generate a broad set of possible research questions and directions, then they converge on the ones most useful given project constraints and goals.

This framework supports research planning in three steps:

Develop an Activity Model — Use one sheet per activity. These are the activities we need to learn about, where problems and opportunities may exist that our design could address.

Identify Targets — For each activity, who should we talk to in order to learn about it?

Define Methods and Questions — For each activity, what research methods make sense, and what specific questions should we ask our targets?

The result is a map of potential research tasks. The goal is not to pursue all the research outlined, but to make conscious decisions about what to do and to have a reference to look to when new questions arise later.

3. Design Analysis: What Do Our Learnings Mean?

The Design Analysis framework helps teams turn raw research data into knowledge that is actionable by design. It helps teams discover patterns that can inform brainstorming and concept development.

This worksheet guides analysis in three steps:

Cluster Stories — What did we hear or see? Group raw observations and data points that illustrate the same problem or opportunity.

Develop Insights — Summarize the cluster. What harms, underlying needs or opportunities are evidenced by these observations?

Define Solution Criteria — What must a solution accomplish?

This framework can help you make discoveries of insights hidden in plain sight—it’s the most exciting part of the design process for me. It doesn’t make answers obvious, but well-formed insights often make the next steps feel inevitable.

4. Concept Development: What Should We Make?

The Concept Development framework helps teams build user-centered stories for new products, services, environments or any other kind of intervention. Concept Development decisions are the choices that increase resolution, detail and refinement of early ideas and prototypes.

This framework guides teams to capture three types of information to help describe an early-stage idea.

Concept Name — Give each idea a memorable name. Naming gives the team a shared language to refer to the idea.

What It Is / Value Proposition — Is it a product, service, or policy? Describe its components and the value it creates. Who benefits, and how?

Sketch — Even the roughest drawing helps. A sketch makes the idea more concrete and often reshapes your own understanding of it.

The framework supports iterative development and evaluation. Rather than waiting for perfection, it encourages teams to put ideas into the world early and improve them collaboratively.

You Still Make the Call

Using this framework won’t make your decisions for you.

It helps you make more informed decisions by getting the team aligned on what’s been learned—and making that knowledge accessible when it matters. It helps you map your options and make sense of the trade-offs. Every decision is a compromise; the sheets make those compromises more visible. But the decisions are still yours to make.

The frameworks can help bring structure to often difficult conversations. For instance, during Concept Development a team will need to decide which ideas are the most promising to move forward with. The frameworks make it easy to create a simple matrix. On one side of the matrix place the criteria established throughout the project, from initial definition to research and analysis insights. On the other side of the matrix, put all the ideas under consideration. Now the team can systematically compare ideas against the criteria. These conversations can help teams align on what each idea actually entails, which criteria matter most, and where gaps in understanding exist that need further investigation.

No framework or process can guarantee outcomes. You can land on a brilliant idea with no process at all. And no amount of process justifies ideas that don’t fit.

What a good framework offers is a fallback when inspiration doesn’t strike. A way to keep moving when the path forward isn’t clear.

“In the Absence of Belief It Is Much Harder To Act”

I don’t know who said that, I’ve never been able to find a source. I think it was one of my early design heroes—maybe Vignelli, Müller-Brockmann, or Dieter Rams—talking about sans-serif typefaces, grid systems, or the power of simplicity. Those guys had strong beliefs and it helped them act decisively.

Wherever it came from, it stuck with me.

These kinds of design rules aren’t “true” in any absolute sense. But believing in them—at least provisionally—helps us move forward in ambiguous situations.

When my own practice shifted from graphic design (where I was definitely in the grid-and-sans-serif camp) into more complex system design, I struggled. I didn’t know what to believe in anymore. I didn’t know how to do the work.

At first, I leaned on the Double Diamond. When I needed something new to believe in, I made all these frameworks and worksheets. I still believe in them, but my belief is loosely held.

“Frameworks: Use Them and Lose Them”

I don’t know who said that either. I think it was in a lecture about learning. The speaker was talking about how babies make sense of the world.

A baby sees a dog for the first time.

“Creatures with four legs and fur are dogs.”

Then they see a cat.

“Hey, there’s another dog.”

But the cat meows. It climbs and gets stuck in a tree. The baby’s framework breaks.

“Oh I get it. There are dogs and there are cats.”

That’s how frameworks work. We build them to make sense of the world. When we encounter something that breaks them, we build better ones.

I teach the Design Decisions framework because I think it’s a useful starting point for graduate students in interaction design. But I don’t expect them to carry it unchanged. I hope they adapt it, reshape it, or even discard it entirely as their own practice deepens.

It’s been 20 years since I was in grad school. The field has changed dramatically. Now, with the rise of AI, the field is shifting so quickly that it’s hard to predict what design practice will even mean in 20 years. I don’t think that’s my lack of imagination.

I feel like we are all flying through thick clouds with no instruments and no one knows where we are headed.

Maybe all this radical change will break my framework. I hope that if it does, I can adapt it—or let it go and find something new to believe in.

If you are interested in learning more about how I use Design Decisions please let me know. I think it provides a solid foundation—but maybe not forever.

Acknowledgments

This framework owes a great debt to the teachings of Chuck Owen, my professor at the Institute of Design in Chicago, whose Systems Approach to design continues to shape how I think and teach. He helped me see design as a rigorous, iterative discipline with the potential to help tackle our biggest challenges. Much of what I teach now is an attempt to carry forward that influence and pass it along to my students.

Thanks to my writing buddies who helped me move this one forward with great feedback and edits:

Rose, Leo Ariel,

, , Malarkodi Selvam, Mak Rahman

I love seeing all your processes! As someone who isn't in design at all, I find it so fascinating how you manage to make sense of the most random stuff to deliver a coherent product!

Love it -- great points & advice on frameworks for decision-making! I can totally see the connection back to Systems Thinking at ID per Prof. Owens :-)

Coincidentally, I had written about "design as decision-making" per my own crossover with Herb Simon's writings at Carnegie Mellon ;-) (Link: https://udanium.substack.com/p/design-as-an-art-of-decision-making) Curious to hear what you think of it. Did you have to read "Sciences of the Artificial" at ID?

And perhaps also relevant to check out is Kevin Bethune's sketch of the design process as a nonlinear activity, which I cited here in a post on "moving from ambiguity to clarity" (Link: https://udanium.substack.com/p/moving-from-ambiguity-to-clarity) -- for me it's one of the most authentic in capturing the dynamic nature of "designing".