Developing Discernment

How can we see what works when we move so fast and we’re not making the decisions?

Only one month into the first semester of their graduate studies, one of my students was already falling far behind.

Then they pasted the assignment into an AI coding tool and caught up on a month of work in ten minutes.

In my career, I’ve learned enough to know how much I don’t know. But I’m never speechless. I can always find a provocative question to ask.

This time, I was stumped.

I asked my students to design a grocery list app. It seems simple and almost boring, but is surprisingly complex when you slow down and look at the details. The class had been working for weeks, diving into the project and sharing several rounds of sketches during each weekly critique. I encouraged students to develop and share multiple ideas for each requirement: how to create lists, how to add and remove items, and how to organize the list for shopping. As a class, we discussed the pros and cons of the different ideas, and each student considered what trade-offs to make in their projects.

The student who was falling behind asked if they could meet with me after class. They had missed several classes, but I was hoping they had made some significant progress even though I hadn’t seen any of their work yet. They appeared tentative and explained that they were not prepared to share in front of the class, but wanted me to take a look. They opened their laptop.

“I’m not sure if this is ok but…”

They explained how they pasted my assignment requirements into Make—Figma’s new AI coding tool—and in about ten minutes had caught up on a month’s worth of work.

They demoed a highly functional piece of software, walking me through how every required feature was covered. All the boxes were checked. But I had many questions about why it ended up the way it did—I wanted to critique the work the same way I had been critiquing their classmates’ projects all semester.

“Why did you make this like this? Why did you put this there? Did you try any other ideas?”

Asking for an explanation of the decisions didn’t feel right, because I knew they hadn’t actually made any decisions that resulted in this output. I could point out specific problems—like clicking “browse” to add items feeling unintuitive, or the lists not being dense or scannable enough—but I wasn’t sure how to teach them to see those issues for themselves.

I don’t discourage using artificial intelligence in my classes, but it hadn’t shown up like this before. Some of my classwork requires writing—I teach students how to frame problems and present their ideas. Language plays a key role here, and that’s where I’ve seen (I assume) AI creeping in. Sometimes students point to a sparkly “AI” button in their product ideas and try to explain what it will do. Usually the answer is something vague: “whatever you want it to do,” or “you can ask it anything,” or “it does everything.” It’s good that they’re starting to grapple with the role of AI in design, both as a tool and as a material. But using AI to build a prototype like this was new—an assault on my core beliefs and values.

Rough and ready. Make to think. That’s what I was taught. Start by making crappy first drafts—cheap, low-fidelity prototypes of several ideas—and continue working on them until one of them isn’t crappy anymore.

One reason designers do this is that high-fidelity prototypes are expensive—in time, tools, labor, and skill. It’s not possible to generate a range of high-fidelity prototypes for every path forward. That’s completely impractical—or it used to be. Maybe now it’s totally possible.

Beyond mitigating the expense of high-fidelity prototypes, the incompleteness of low-fidelity prototypes plays another crucial role. A sketch, a paper prototype, a rough wireframe—these artifacts leave space and invite interpretation. It’s like squinting: blurred details allow the imagination to fill in the gaps and for you to consider multiple paths forward. When the fidelity is low, different people can look at the exact same prototype and see different possibilities. The conversation becomes: What matters most? What is this trying to be? What should it become?

Making things helps define the problem you’re trying to solve.

There’s always been pressure to compress that process and get something done as quickly as possible. When I was a student, I used to flip through design awards books and magazines looking for ideas to steal—ways to get to something that looked real faster. Then Dribbble came along, and you could download someone else’s Photoshop file as a starting point for your project. Later, Figma’s Community tab became the go-to resource for ready-made, ultra-high-fidelity starting points. We’re always trying to go faster, make higher-fidelity prototypes more quickly. AI is the next step in that evolution. But now we’re on a very steep part of the technology development curve. So steep that AI threatens to circumvent the traditional design decision-making process almost entirely.

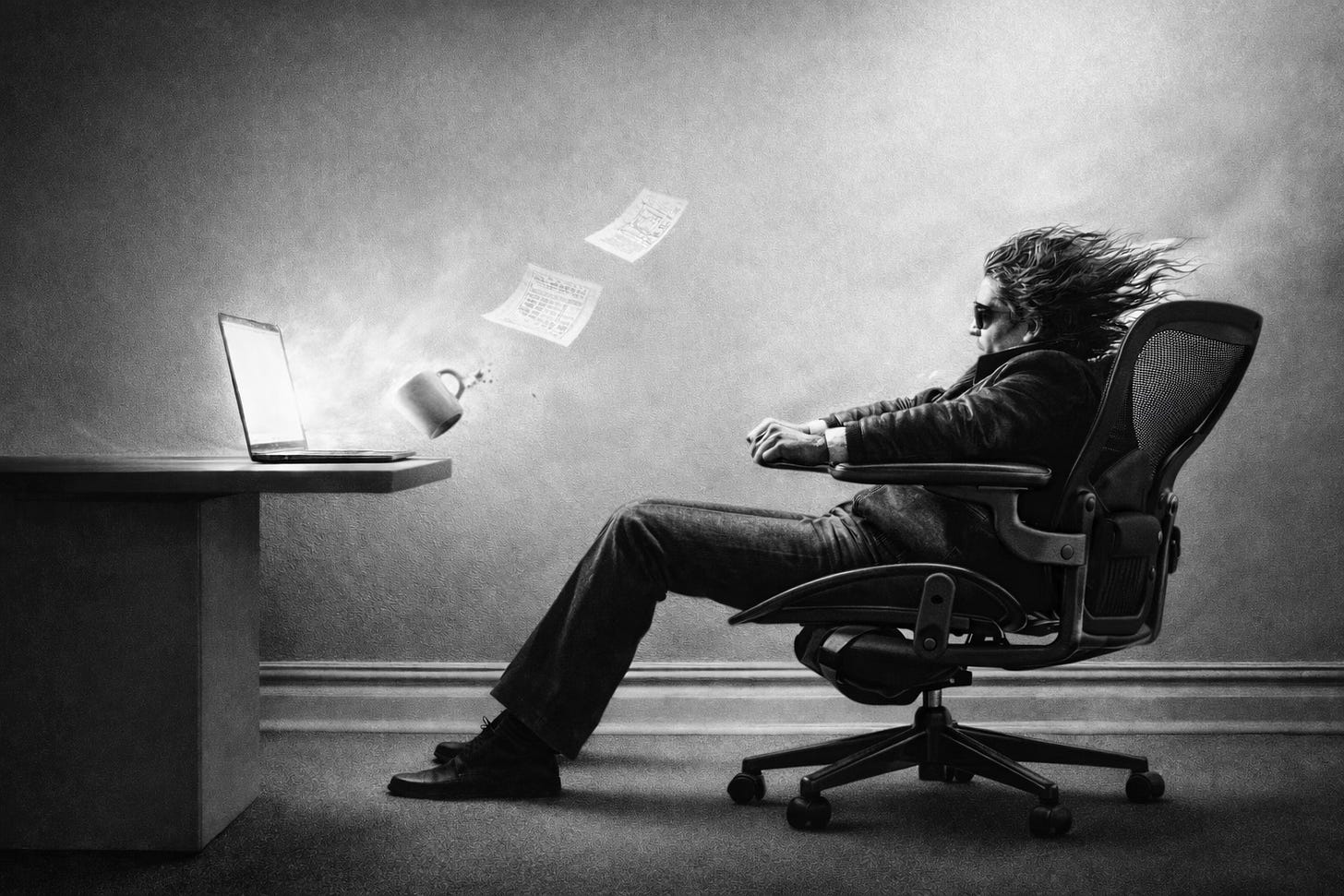

How can we still learn to see what works when AI makes all those decisions?

Now that prototypes are so cheap, I will focus even more of my classes on problem definition and helping students gain a systems perspective. I want students to practice looking at problems from multiple angles, designing prompts to explore each one.

And I don’t want the machines to force students to jump straight from prompt to final outputs—no matter how much confidence the machine has in its answers. I’d like to see fuzzier, less defined sketches. Something to react to and interpret, not just accept. I want tools that explore by default—showing multiple directions, surfacing tradeoffs—rather than handing students a single polished answer that is more difficult to question.

At the same time, I want to protect some space from speed. I think some learning takes time and feels inefficient. I want students to experience the satisfying work of deciding, revising, and developing judgment. If AI collapses the space from start to finish, then I want part of my teaching to stretch that back out again, creating room for discernment to develop—and for students to learn the joy of making something from nothing.

I hope the next student who asks me to stay after class shows me the five prompts they tried—and what they learned by comparing the tradeoffs.

Because moving efficiently isn’t enough. We also have to get somewhere we actually want to be.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my writing buddies who read one of the many drafts of this story:

Michael Dean, Rik Van Den Berge, Isaac William, Dominik Gmeiner, Mahmudur Rahman