Welcome to My Ears Ring and I Can’t Sleep, where I chronicle my tiny misadventures at the edges of the underground music scene.

I am stuck to the wall. Stuck like wallpaper. I’m not even sure whose house this is. I flashed the invitation at the door and we walked right in. No questions.

I feel self-conscious and out of place. I don’t know what to expect, other than some kind of mayhem.

In a previous post1, I wrote about interviewing the late Steve Albini—underground rock’s most confrontational and opinionated icon. I had driven to Chicago from Cincinnati with my editor, Chandler2, for a sit-down at Steve’s home recording studio with him and his band Shellac.

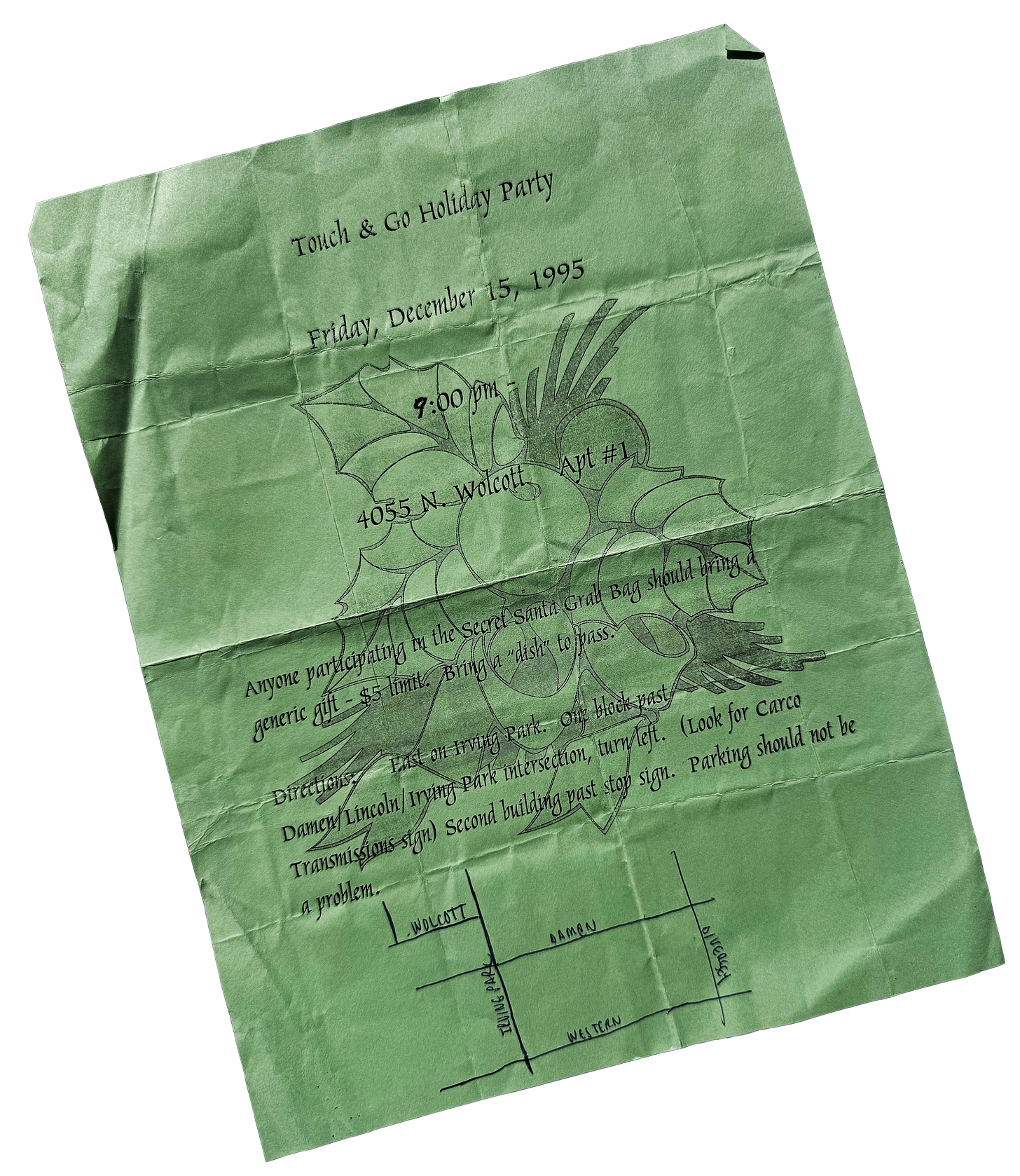

After the interview, Steve gave me two records as a parting gift. What I cut from that story: he also invited Chandler and me to the Touch and Go Records holiday party.

Chandler didn’t want to attend the party. I dragged him there anyway…

I’m trying to blend into the wall. I avoid house parties—but they are nearly unavoidable in college. I have learned how to be at one but unnoticed. Tonight I’m making an exception. There is no way I am missing the Touch and Go Holiday Party.

Chandler is falling asleep on the couch.

Touch and Go is my favorite record label. An independent label based in Chicago, they released the records from the bands that became the soundtrack of my life: Shellac, Silkworm, Arcwelder, Don Caballero, The Jesus Lizard, Girls Against Boys—to name a few. I have no idea how I developed my taste for abrasive, radio-unfriendly guitar music. No idea how many of these bands will be at the party tonight, either. But seeing—or maybe meeting—just one of them would add to the dreamlike quality of this trip to Chicago to meet Steve Albini.

David Yow from the Jesus Lizard makes a big, predictable entrance.

The last time I saw David, he was standing on top of a stage monitor with his pants around his knees, screaming into a microphone he was trying to swallow. His stage presence is intense, stumbling, chaotic, and alcohol-fueled—and while his arrival at the party is slightly less enthusiastic, it’s still exciting.

He’s cartwheeling through the crowd with exaggerated gestures of affection and goodwill toward everyone in the room.

I’m at a holiday party with David Yow? Confronted with the opportunity, I’m not sure I actually want to meet him. I’ll watch from a safe distance.

The entrance of Girls Against Boys is slo-mo and cinematic. Soon to “graduate” from Touch and Go to Geffen—a “real” major label—GvsB already carried themselves with a different kind of confidence, swagger, and star power than the rest of the revelers.

They toss their big coats—but not their blingy sunglasses. Other partygoers scramble to care for their outer layers as the band glitters and floats through the crowd, offering brief acknowledgments: finger-pointing and, one imagines, winks from beneath the dark shades.

Yeah, maybe I don’t need to meet those guys either. Watching them float around is cool, though.

Chandler rises from the couch, tired, complaining, and anxious to leave. We’d driven to Chicago in his Jeep Cherokee, and now he’s threatening to take off—leave me here, with no obvious way to get home.

He’s the boss at the magazine where I’m moonlighting during college, and he gives off a real Let’s Fucking Go vibe—but I’ve always known it’s an act. He works hard to project the image of a connected socialite—a guy who’s down for anything, up for whatever, whenever. He’s posing.

He did not want to be at the Touch and Go holiday party.

He would give me a hard time if he heard I fell asleep on the couch at a rock-and-roll holiday party. Teasing me—and anyone else he considered lower status—was his favorite pastime. “Go hard or go home,” he’d say. Today it’s go home so he can go to sleep, I guess.

When I met Steve Albini, I was scared. I was walking into the lair of a wild, unconstrained animal. Albini was known for unforgiving fanzine screeds against bands, record labels, music journalists—anyone who couldn’t meet his impossibly high ethical standards. What kind of teasing would I encounter from this guy?

During college, Steve Albini started a band called Big Black—a platform engineered for aggressive confrontation. Big Black’s drum machine-driven music is punishing and unrelenting. The lyrics explore nightmarish corners of the human experience—child abuse, alcoholism, cattle abattoirs, for instance.

Michael Azerrad profiles the band in Our Band Could Be Your Life, his essential chronicle of the indie underground from 1981 to 1991. In the book, Albini explains the origin of the band’s name:

“It was just sort of a reduction of the concept of a large, scary, ominous figure. All the historical images of fear and all the things that kids are afraid of are all big and black. That’s all there was to it.”

When I interviewed him, I asked why the band he started after Big Black was called Rapeman3. It took real courage to ask. I wasn’t sure I wanted to know the answer—and I definitely didn’t want to provoke him. But I couldn’t wrap my head around the choice. How could anyone name a band that?

His answer? It was named after a Japanese comic-book character—an anti-hero who leapt from rooftop to rooftop, breaking into windows at night to “punish” women. He thought the absurdity made it funny. “It was a joke,” he said.

Shellac’s drummer, Todd Trainer, chimed in sarcastically: “What, you don’t think that’s funny?” It was clear I didn’t get the joke.

Apparently, naming a band Big Black wasn’t confrontational enough—he had to turn it up a notch.

I was afraid I’d provoked the beast—and braced for a lacerating response. Yeah, I was scared.

But instead of a verbal mauling, Steve gave me two records and invited me to a holiday party. He teased me a little during the interview, but I laughed with him. He was a confrontational and unapologetic guy who didn’t care much what other people thought. But he was also kind and generous.

Chandler’s teasing didn’t bother me. His family money was bankrolling the magazine that made meeting Steve possible. I could handle his weak jabs for that.

But he is being so insistent. He wants to leave, and the party has barely started. Eventually, his moaning, whining, and complaining wear me down, and I capitulate.

We head out to his car just as the party is winding up. Chandler hands me the keys and takes the passenger seat, passing out before I get the car started.

Looks like I’ll be driving.

It’s very dark in the middle of the night on a highway in Indiana.

I’m making good progress, convincing myself that getting home tonight isn’t entirely bad, when I feel the car shudder.

The glowing dashboard says we’ve got a quarter tank of gas, but I hear the sound of a car running out of fuel. I’ve only heard this sound in cartoons, but I know that’s what’s happening.

I shove Chandler awake.

“Dude! A quarter tank means empty in my car!” Even emerging from his stupor he makes it clear our predicament is my fault.

It’s very cold in the middle of the night on a highway in Indiana in late December.

With the hazard lights on, Chandler and I stand in the breakdown lane. All the traffic is semi-trucks, and no one shows any indication of stopping.

I’ve given up hope of making it home that night when a small hatchback pulls into the breakdown lane a couple hundred feet ahead.

I meet the driver halfway between our cars and explain the situation. He’s completely unremarkable—forgettable, even. He listens, nods, and offers to take me to the nearest gas station, where—presumably—I’ll be able to resolve the issue.

Driving away in the mild-mannered stranger’s nondescript car, I imagine this is the opening scene of a low-budget slasher movie. I’ll be the first nameless victim—killed off before the title sequence. I wonder if I’ll make it back to Chandler and the Cherokee.

I lean a little farther from the driver’s side as he strikes up a conversation. He’s on his way home from a weekend Renaissance faire in Wisconsin.

The perfect cover.

When we arrive at the nearest service station, the attendant tells me he’s closing up in five minutes and can’t lend me a container for gas. There’s nothing suitable for sale either.

Undeterred, I buy a gallon of milk, step into the parking lot, and pour it down the sewer drain. I pump the empty milk jug full of gasoline and return to the store to pay for the gas and a long-necked bottle of engine treatment.

The Ren Faire enthusiast returns me and my acquisitions without incident and I empty the treatment bottle into the gas tank. The long-necked bottle is able to bypass the safety mechanism of the gas tank and the next step is to somehow remove the bottom of the bottle—creating the funnel I need to get the gas from the milk jug into the tank.

“I can help with that,” offers the “Good Samaritan.”

He steps to the back of his hatchback and pops the trunk.

After the brief distraction of my roadside MacGyvering I’m snapped back to the plot of the horror movie. He’s luring me closer to the trunk, so he doesn’t have to drag the body quite so far.

Inside the trunk, there’s a thick wool blanket spread across the floor.

To wrap me in.

He tosses back a corner of the blanket, revealing a collection of twenty or thirty Renaissance-period blades. He’s carrying swords, cleavers, daggers—one for every conceivable medieval purpose, all laid out for easy access.

I hold my breath as he offers me my pick from the collection.

Suspicious, I reach into the trunk and select a blade that will do the job. The smooth steel glints in the light from the trunk's dome light as I carefully extricate it from its blanketed storage place.

The sword-collecting motorist from the Renaissance faire covers the remainder of his collection, closes the trunk, hops back into the driver’s seat, and takes off.

I’m standing on the side of the road—holding a rather large broadsword, an empty bottle of engine treatment, and a milk jug full of gasoline. I guess he won’t miss one sword.

I consider the best method. Careful sawing? A full-bodied overhead swing? On my knees in the gravel at the side of the road, I pin the bottle to the ground by its neck and raise the blade above my head. With a swift downward stroke, I relieve the long-necked bottle of its bottom, creating the required funnel.

The gassed-up milk jug is easily emptied into the vehicle, and that’s how I saved Chandler’s ass and got us home to Cincinnati.

I like to imagine someone, weeks later, discovering the remains: an amputated engine treatment bottle, a gasoline-scented milk jug, and a large, Renaissance-period broadsword—discarded on the side of the highway in Indiana.

I barely knew Steve Albini, but he gave me so much that is so important to me. The art he made, the art he helped others make; the Appliances-SFB records he handed me; the invitation to the holiday party.

I feel Steve gave me this story—however indirectly. I’ve been telling it for 30 years and I still love telling it. I like to think Steve would have appreciated it.

Thank you, Steve Albini.

Acknowledgments & Footnotes

Many thanks to my fellow writing buddies for reading and offering feedback on one of the many drafts of this essay:

My previous piece on meeting Steve Albini: A Brilliant Fellow with a Lacerating Wit

Chandler isn’t his real name. No need to call him out publicly for his weak teasing.

Terrible name for a band, but they did an amazing cover of ZZ Top’s “Just Got Paid.” Albini did eventually own up to making mistakes.

…dang i didn’t see the double layer on first read but your night into the big black back home was there all along…some hidden menace looming but never actualizing and in the end not real at all…EXCEPT there it is on the side of the road left for someone else’s imagination to maybe even be their big black…

I really enjoy reading about your adventures while you were at UC. I sincerely hope your children will tell you stories about things/events you didn’t know (many years after the fact, of course).

This post was fun to read and very well written. You should have kept the sword!